The Lawlessness of TRL: A Critical Lens

A look back at the cultural impact of MTV's Total Request Live.

Musings of an Anxious Millennial Writer #05: Examining the socio-political impact of an MTV show.

With his imperfectly manicured black nails, he clutched the microphone close to his chest, the sadness consuming him despite his ability to hold back the tears. He was wearing black, but that wasn't unusual. However, this time felt purposeful: it was a time of mourning. The studio audience lacked its trademark exuberance. The tone was somber, and everyone knew this would be a show like no other.

Joe C. had tragically passed, and Carson Daly displayed the most emotion he ever had and probably ever would. I was witnessing, in real-time, a moment that would never be replicated, a time capsule of an era. Television history that few would ever remember less they are in conversation with me, the one person who insists on referencing it whenever the opportune (or more likely inopportune) moment presents itself.

But at the time, it was just another (albeit weird and tonally off) episode of Total Request Live. Total Request Live, or TRL as the hip kids called it, may go down in history as a seminal show in MTV’s legacy. The last gasp in a now-bygone era of broadcasting music videos, though one that seemed like it could return the network to its former glory. Yet it was so much more than just an MTV show; its impact—if only on me personally—should not be understated.

In short, TRL was the goddamn Wild West. Where else in popular media and in civilized society could the likes of Korn and Blink-182 hobnob with 98 Degrees and Jordan Knight? All were welcomed with the same acceptance and amused indifference to their music video overlord, Daly. Long before political talking heads were tsk-ing and sweating over “WAP,” preteens were gleefully singing along to a song that likened sex to an act on the Discovery Channel. We all wanted to do it doggy style so we could both watch X-Files, even if we didn't know what that meant. But damn if those men in their monkey suits didn't enchant us. I could wax poetic about The Bloodhound Gang endlessly (and I may just somewhere down the line). Still, their presence on the show that acted as the official tastemaker (so long as you had a hella cool music video) in the late ’90s and early 2000s deemed them cool—nay—pop enough to climb their way up the leaderboard.

Watching TRL became an after-school ritual for me. I'd hedge my bets on what music video would win and audibly groan when “Baby One More Time” again secured the number one spot. I was not a child of discerning taste at this point in my life. I was only just beginning to differentiate my musical taste from the adults around me. No longer into the Best of the 1974 compilation CD my aunt gifted to me a few years earlier, I began to seek out the newest NOW That’s What I Call Music’s and pop and hip-hop compilations burned on cheap silver discs and sold for $3 at the local flea market. I was probably into it if it was on frequent rotation on MTV or featured on a Fox Family spotlight.

And yet TRL instilled in me something I hadn't yet experienced: a disdain for most contemporary pop music. Once a song reached—and especially maintained—a spot at number one, I was likely to develop an intolerance that would sometimes evolve into loathing. Britney Spears was often the subject of my ire for this very reason (until she dropped the “Stop!” remix of “Crazy,” which was, admittedly, fire). I'd watch religiously nonetheless, rooting for the downfall of all these pop kings and queens, hoping for salvation even if it was only in the form of a different, lesser pop star. (Mandy Moore never got her flowers, in my humble opinion.)

That's when things got interesting.

Despite it being a glorified popularity contest, artists like Korn and Kid Rock could sing and growl their gibberish to the top of the charts. Pop princess-loving cheerleaders and outcast nu-metal kids could coexist—maybe not in the cafeteria, but by way of television screens, Monday to Friday. Shared, but separate. It was a homogenous melting pot of varied tastes and backgrounds. Carson Daly showed us what a fair democracy could truly look like.

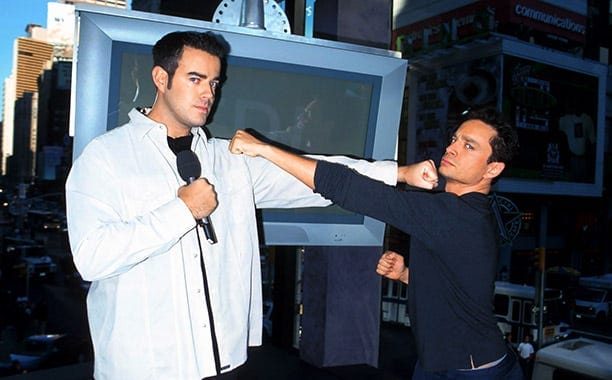

I don't think I would ever look back at my adolescent and key developmental years and attribute a lot, or really any, of who I am to Tom Green, but thanks to him, I started to embrace the wonder and chaos of disrupting the system. In the ultimate testament to grassroots organizing, Tom Green’s “Bum Bum Song” forced his way onto the revered list and wouldn't stop until it achieved world domination, AKA the high, holy number one spot. The subset of folks who returned to MTV to watch Jackass and The Tom Green Show began infiltrating the pop music countdown from the inside. They gathered, even if not in person, to honor “Rock the Vote” and dismantle the pop-riachy.

Then when “The Bum Bum Song” conquered that heralded top spot, MTV urged Tom Green to retire it, never to appear on the show again. Effectively smashing to bits any illusion of true choice we once had. And then Eminem showed up, made a mockery of all of it, and unified viewers with rampant misogyny and homophobia. But it was nice while it lasted!

In a world where concerns about whether our votes truly matter are valid and time put in fighting the good fight feels like drops in the bucket, reminiscing about TRL makes me realize that being relentless and active about what you care about still matters. Your voice still matters. …Until someone loud and hateful comes around to galvanize misanthropic white boys, then you're kinda fucked.

OK, maybe I don't have as smart of or hopeful of a metaphor here as I thought. But hey, man, I can't always be poignant. To quote another iconic MTV persona (for me personally), “I can't be perfect every time out. I'm not Ozzy Osbourne.” But that’s a whole story for another time.

Also, whatever happened to Jesse Camp??